A History of Racial Covenants in Minneapolis and Beyond

5/7/22-Written by SJ

Racial covenants were first introduced in the early 1900s as a legally binding way to keep people of color out of “desirable” neighborhoods, essentially creating segregated neighborhoods in areas where they otherwise may not have existed. As a result of these covenants, the journey to homeownership and equitable communities has become significantly more difficult for people of color.

These covenants were written into property deeds and explicitly prohibited homeowners from selling or renting their houses to people of color. The language of racial covenants tended to differ regionally and changed depending on the racial makeup of cities and states, as well as the climate of white fear during the time they were signed.

The University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice Project dated Minneapolis’ first racial covenant back to the 1910 sale of a home in South Minneapolis. That particular deed dictated that the "premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent."

According to Mapping Prejudice researchers, the wording of racial covenants wasn't always as specific as that example. Another covenant that frequently appeared on Minneapolis deeds stated, “the said premises shall not at any time be sold, conveyed, leased, or sublet, or occupied by any person or persons who are not full bloods of the so-called Caucasian or White race." This turn of phrase was just vague enough to prohibit any and all people of color from purchasing a covenanted house.

During World War I, Black communities moved to Northern states in large numbers from the South, marking the beginnings of the Great Migration. It is estimated that nearly 6 million members of the Black community moved North between then and the early 1970s, settling in inner-city areas such as Minneapolis. This migration fueled the popularization of racial covenants and, eventually, white flight.

During the 1920s and 1930s, racial covenants were not uncommon, but it wasn’t until shortly after President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the National Housing Act in 1934 that the practice was popularized. Created on the heels of the Great Depression, the National Housing Act was intended to help make homeownership affordable (for white people) and decrease the likelihood of foreclosures (for white people).

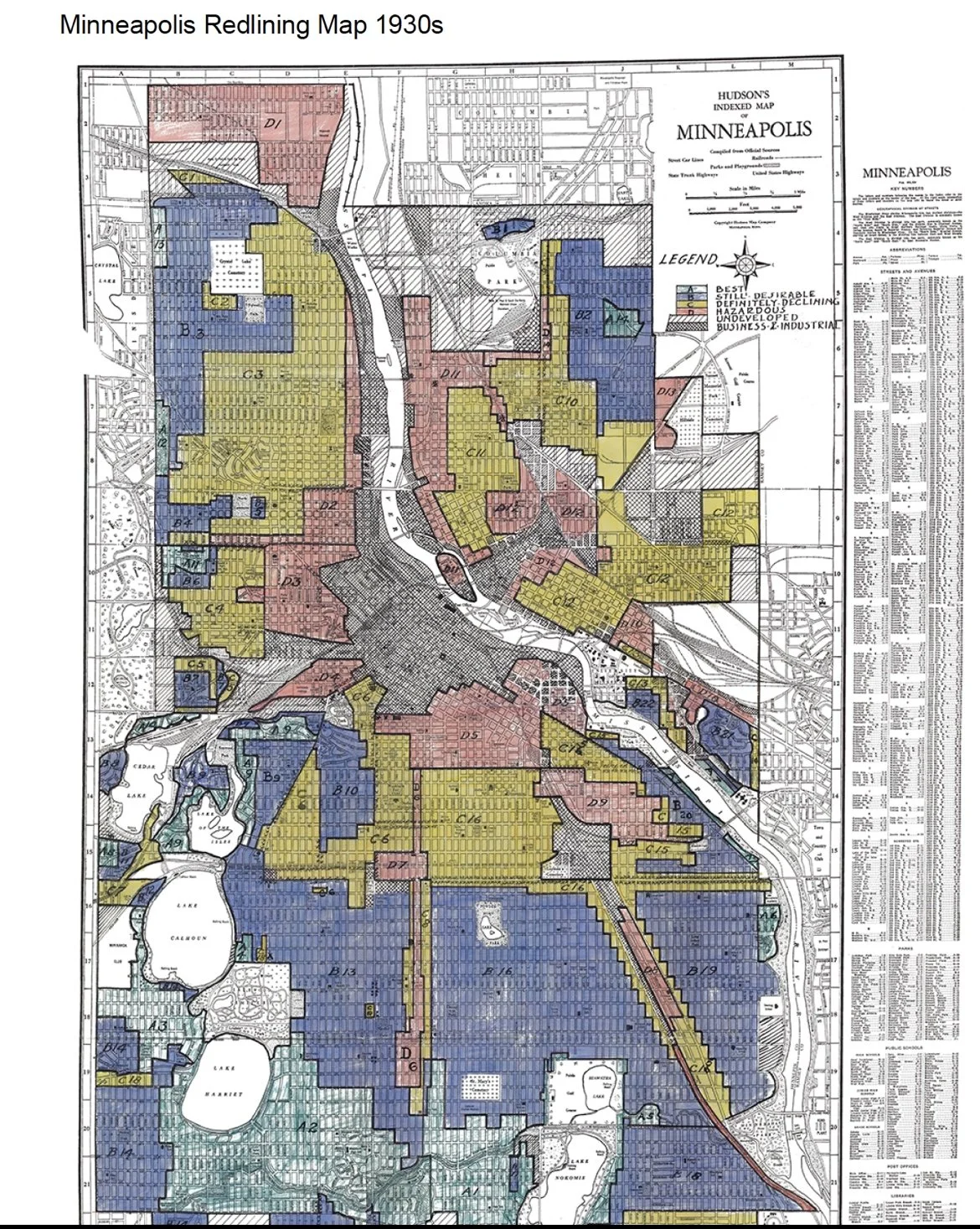

The National Housing Act did help the housing crisis but it also created the segregationist practice of “redlining.” The Federal Housing Administration drew up a series of maps designating ‘desirable’ neighborhoods from ‘hazardous’ ones, in terms of mortgage lending risks. These designations were color-coded with green indicating the best neighborhoods and red indicating a high risk. Not surprisingly, neighborhoods in wealthy, white areas and upper-crust suburbs usually received the lowest risk ratings, while inner-city neighborhoods where communities of color and those who were economically disadvantaged resided were “redlined” to indicate high risk.

The Federal Housing Administration surmised that Black and Brown people existing near white neighborhoods (or, God forbid, in them) lowered property values. For the record, it turns out their claims were baseless and created with little to no discernible research. In reality, people of color were often forced to pay more for homes in “nicer” neighborhoods (driving housing values up) because they lacked the same resources, funding assistance, and opportunities white communities had access to.

To avoid being “redlined,” white homeowners, communities, and developers began widely adopting the practice of racial covenants, ensuring their property investments would remain profitable. It was incredibly unlikely, if not impossible, for a neighborhood with homes ‘protected’ under covenants to be “redlined.”

Both “redlining” and racial covenants were federally banned in 1968 after the passing of the Fair Housing Act which stipulated it was no longer legal “to negotiate for the sale or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, or national origin.”

The Mapping Prejudice Project has recently discovered evidence of more than 8,000 old racial covenants in Minneapolis property titles.

The City of Minneapolis’ website states, “In 2010, Minneapolis’ population included 69% white residents and 19% Black residents. However, in the neighborhoods where racial covenants had been common, the population was still 73-90% white. Similarly, the neighborhoods to which Black residents moved during the years when racial covenants were used had present-day populations of 43-62% Black residents.”

The city’s website also points out that in 2019 only about 25% of the Black community in Minneapolis were homeowners, earning it the distinction of “the lowest [Black homeownership rate] of any metro area in the nation.”

Sadly, this tracks considering lenders such as Wells Fargo (one of the largest mortgage lenders in the country) still appear to be utilizing the old “redlining” practices. Over the years Wells Fargo has been the subject of numerous discrimination cases. Last month court documents accused the financial institution of “modern-day redlining” after Bloomberg reported that in 2020 Black homeowners who applied for refinancing with Wells Fargo were approved at a rate of 47%. White homeowners, on the other hand, were approved 72% of the time (read the full story here). It’s worth noting that Wells Fargo certainly isn’t the only bank to be accused of such practices.

Today, neighborhoods of color, and formerly “redlined” communities, tend to receive fewer resources, funding, programming, and green spaces. The people living in these neighborhoods are still less likely to have access to necessities such as healthcare, reliable transportation, nutritious foods, and equitable education.

”Redlining” and racial covenants teamed up to keep white neighborhoods white. The two policies worked in tandem, making it difficult for people of color to become homeowners and trapping them in undesirable neighborhoods.

The legacy of these racist policies continues to negatively affect neighborhoods of color today, creating substantial racial disparities in homeownership, mortgage accessibility, generational wealth, and quality of life. White communities, on the other hand, continue to profit from the lasting effects of redlining.

Do you own a home with an old racial covenant still attached to its deed? The City of Minneapolis is now offering to remove the outdated covenants for free via its Just Deeds Program. Learn more here.